How Do You Tweak SIMD Code for Performance?

SIMD stands for Single Instruction Multiple Data. As the name suggests, unlike scalar assembly instructions that act on one element at a time, SIMD instructions act on several elements simultaneously.

The advantage is that with the right problem and done correctly, it can significantly speed up the code as it skips many a conditional check. However, optimizing SIMD instructions is anything but straightforward.

Where to Start?

When writing this document, I struggled to find easy rules of thumb. The truth is, most of my work has been ad hoc iterative changes involving extensive trial and error. Our philosophy was that it is better to try 10 different plausible solutions than to have one perfect one.

In many ways, it’s like finding an optimal way to speedrun a video game: balancing a myriad of factors, each with its advantages and disadvantages. Some issues only came up once during the projects. Additionally, the compiler might not always output assembly code that resembles what you wrote.

First SIMD Task Example

To illustrate, my first SIMD task was to test, benchmark, and extend this sketch:

Computing the UTF-8 size of a Latin-1 string quickly (AVX edition)

into code that could be merged into simdutf proper.

To optimize the sketch, I unrolled it further until I found a sweet spot. I also tried swapping instructions, but since the original instructions were already cheap, it didn’t make much of a difference.

I ended up with something like this:Ahoy Matey! The issue of Port contention

When it came to AVX-512, unrolling didn’t have much of an effect, and the AVX-512 version performed similarly to its AVX2 counterpart.

The C++ benchmarks in simdutf have a ‘raw speed’ counter, as well as counts for instructions per cycle (IPC) and instructions per byte (IPB). Ideally, IPC should be high and IPB should be low. However, in this case, the lower instruction count per byte was accompanied by a decrease in IPC, indicating potential port contention.

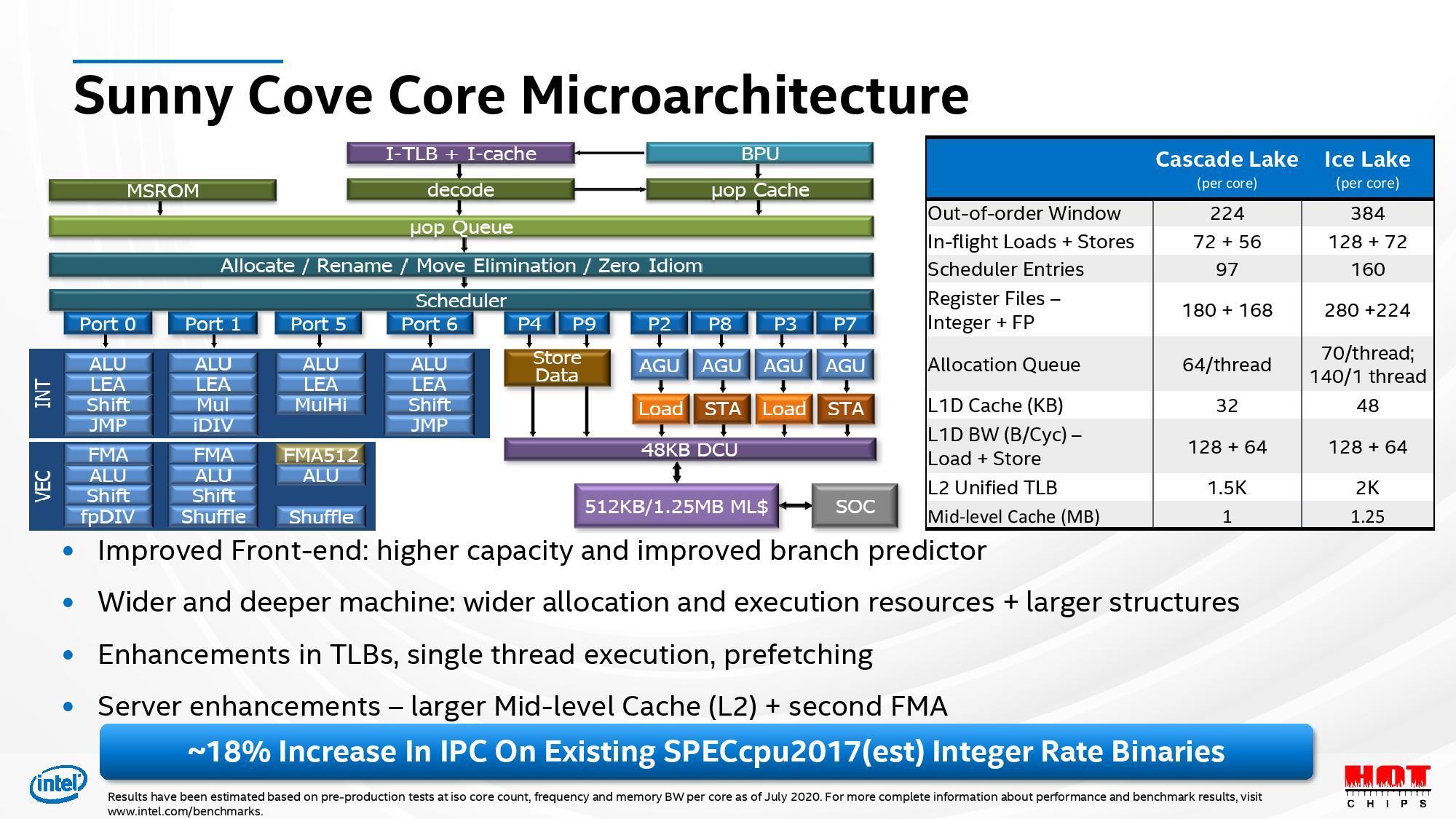

Modern architecture doesn’t execute instructions sequentially as they appear in source code; instead, it has multiple execution units that process data in parallel.This diagram depicting the Sunny cove microarchitecture is worth a thousand words:

We need only to pay attention to the light blue boxes beneath the different ports. They are dubbed 'EUs' or execution units. We can see that each of them is assigned a port and a particular role (such as for example multiplication or shuffling bits around).

Analyzing the main loop assembly code with the UiCa code analyzer revealed that, although the instructions were cheap, they were all hogging port 0. In other words, it is not enough to pick cheap instructions: if they are numerous, it becomes nescessary that they be varied.

We could have worked to relieve the pressure on port 0, but Daniel deemed the performance acceptable and suggested I move on.

A counterintuitive example

My next task was to optimize simdutf’s count_utf8 function. Here were the initial results:

Before:

0.509 ins/byte, 0.349 cycle/byte, 8.943 GB/s (1.4 %), 3.119 GHz, 1.461 ins/cycle

1.478 ins/char, 1.012 cycle/char, 3.083 Gc/s (1.4 %), 2.90 byte/charAt first, I applied the same approach from the blog post but got worse results:

0.909 ins/byte, 0.554 cycle/byte, 5.620 GB/s (0.9 %), 3.111 GHz, 1.642 ins/cycle

2.636 ins/char, 1.606 cycle/char, 1.937 Gc/s (0.9 %), 2.90 byte/charNot knowing what to do, I dug into the Intel Intrinsics Guide. There are thousands of instructions, but I discovered that AVX-512 had a vectorized popcount instruction that did the same thing as its scalar counterpart. I reasoned that with more unrolling, I could avoid context-switching costs and keep everything in SIMD registers.

simdutf_warn_unused size_t implementation::count_utf8(const char * input, size_t length) const noexcept {

const uint8_t *str = reinterpret_cast(input);

size_t answer = length / sizeof(__m512i) * sizeof(__m512i); // Number of 512-bit chunks that fits into the length.

size_t i = 0;

__m512i unrolled_popcount{0};

const __m512i continuation = _mm512_set1_epi8(char(0b10111111));

while (i + sizeof(__m512i) <= length) {

size_t iterations = (length - i) / sizeof(__m512i);

size_t max_i = i + iterations * sizeof(__m512i) - sizeof(__m512i);

for (; i + 8*sizeof(__m512i) <= max_i; i += 8*sizeof(__m512i)) {

__m512i input1 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i));

__m512i input2 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + sizeof(__m512i)));

__m512i input3 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + 2*sizeof(__m512i)));

__m512i input4 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + 3*sizeof(__m512i)));

__m512i input5 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + 4*sizeof(__m512i)));

__m512i input6 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + 5*sizeof(__m512i)));

__m512i input7 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + 6*sizeof(__m512i)));

__m512i input8 = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i + 7*sizeof(__m512i)));

__mmask64 mask1 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input1, continuation);

__mmask64 mask2 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input2, continuation);

__mmask64 mask3 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input3, continuation);

__mmask64 mask4 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input4, continuation);

__mmask64 mask5 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input5, continuation);

__mmask64 mask6 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input6, continuation);

__mmask64 mask7 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input7, continuation);

__mmask64 mask8 = _mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(input8, continuation);

__m512i mask_register = _mm512_set_epi64(mask8, mask7, mask6, mask5, mask4, mask3, mask2, mask1);

unrolled_popcount = _mm512_add_epi64(unrolled_popcount, _mm512_popcnt_epi64(mask_register));

}

for (; i <= max_i; i += sizeof(__m512i)) {

__m512i more_input = _mm512_loadu_si512((const __m512i *)(str + i));

uint64_t continuation_bitmask = static_cast(_mm512_cmple_epi8_mask(more_input, continuation));

answer -= count_ones(continuation_bitmask);

}

}

__m256i first_half = _mm512_extracti64x4_epi64(unrolled_popcount, 0);

__m256i second_half = _mm512_extracti64x4_epi64(unrolled_popcount, 1);

answer -= (size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(first_half, 0) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(first_half, 1) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(first_half, 2) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(first_half, 3) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(second_half, 0) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(second_half, 1) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(second_half, 2) +

(size_t)_mm256_extract_epi64(second_half, 3);

return answer + scalar::utf8::count_code_points(reinterpret_cast(str + i), length - i);

}

0.353 ins/byte, 0.272 cycle/byte, 11.491 GB/s (3.8 %), 3.130 GHz, 1.296 ins/cycle

1.024 ins/char, 0.790 cycle/char, 3.961 Gc/s (3.8 %), 2.90 byte/charGenerally, you don’t want to unroll as much as eight times, but in this case, the benefit of keeping everything in SIMD registers with AVX-512’s popcount outweighed the downsides of excessive unrolling.

Final Thoughts

I hope this illustrates that SIMD programming is like min-maxing a gacha game: there are always educated guesses, but you can never be completely sure it will work out until you try it. It’s full of little tricks that, while not groundbreaking on their own, accumulate over a project.

It’s well worth trying 10 plausible solutions rather than sticking to one perfect theory. Besides writing tests and building infrastructure, exploring all sorts of plausible paths and optimizations has been my bread and butter for the past year and a half.